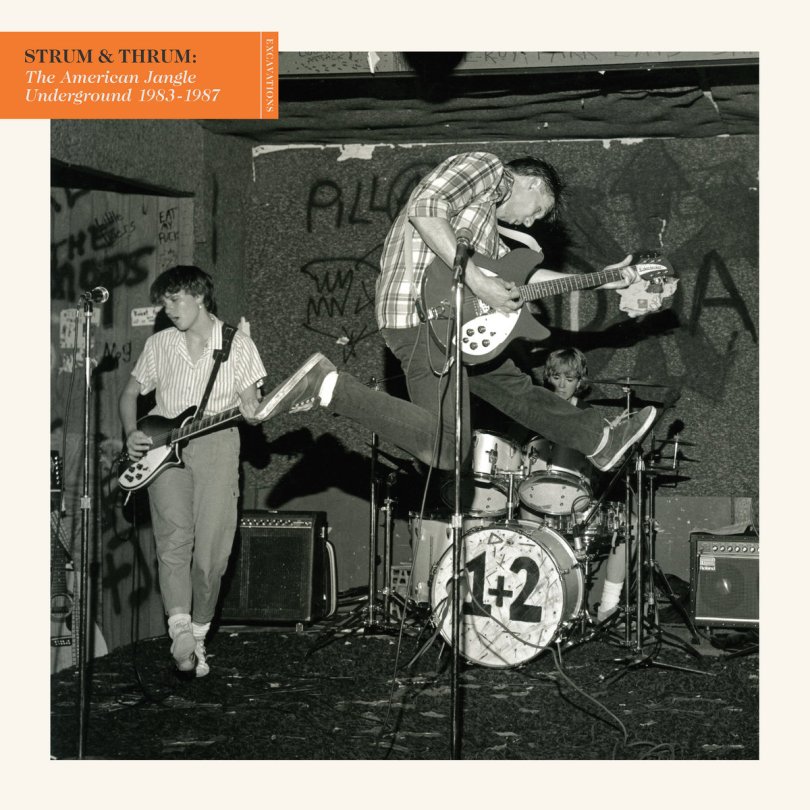

Cover image via Bandcamp.

I’ve long been of the opinion that, of the big grunge bands to come out of the Seattle scene in late 80s and early 90s, Nirvana was — and remains — in a class of their own.

For me, their sound remained significantly unique as opposed to the more hard rock tendencies of the other big grunge acts like Soundgarden or Pearl Jam. I follow observations made by music journalists like Michael Azzerad in attributing this to frontman Kurt Cobain’s long standing embrace and appreciation of pop music. That inspiration, coupled with the foundational roots in hardcore punk, helped Nirvana perfectly bridge the gap between the underground sound and a mainstream audience.

Cobain often made note of some of his favorite bands, which for teen Raul became a vital gateway into the world of alternative music. He of course noted fellow artists that contributed to the grunge scene like Mudhoney and the Melvins, but it was his name-dropping — as well as song covers — of the seemingly-less celebrated twee/jangle pop icons like the Vaselines and Beat Happening that held my attention.

What’s always been interesting to me is that, in that twee and jangle pop sound, I gravitated towards one particular quality — its power to evoke nostalgia. Now, with the release of Strum & Thrum: The American Jangle Underground 1983-1987, Captured Tracks, a label that has built its house upon sonic nostalgia, brings a collection that sheds light on an often-overlooked moment in U.S. music history.

In many ways, the Captured Tracks sound has always owed a debt to music that takes its cues in mirroring sounds from the past, so it makes sense that the label would start at the source for their first release on their new Excavations reissue project. The result is an invaluable examination of a subterranean musical movement that has, until now, largely subsisted in the discount bins of record stores in small towns across the U.S.

The genre itself occupies an interesting area as it pertains to other music movements at the time. While bands in the UK were gaining the sort of traction they’d be hailed for in hindsight, U.S. jangle pop grew with a strong DIY ethos mirrored by the burgeoning hardcore punk scene, but with strong inspiration derived from acts like R.E.M. Indeed, this mesh of influences can be heard throughout Strum & Thrum — there’s the largely arpeggio-driven structure typical of the jangle sound, but tempos and even chords that bear the markings of hardcore make themselves heard on tracks like “I’m in Heaven,” and “She Collides With Me.”

This quality — of a form of punk stripped of its, at the time, more macho/aggro associations — results in a sound that evokes, at least for my 90s kid ears, a sort of idealization of a past steeped in a kind of childlike sincerity. It’s lighthearted but genuine, unique but at the same time familiar.

However, there is a part of me that wonders where this nostalgia and yearning for this past comes from. While listening to this album and attempting to write this entry, an interesting realization came to me. I’ve long attributed my appreciation for this music to a sense of nostalgia, but the question becomes: is it really mine? I didn’t grow up around this music necessarily. Perhaps it was through other media sources from when I was a kid, like television or film, but I’m not certain.

Then I stumbled upon a new (to me) concept recently — sehnsucht. From what I’ve gathered, an aspect of this feeling deals with a sense of nostalgia for a utopian, or perhaps romanticised, vision of the past. I think a lot about nostalgia these days, particularly within the parameters of Mark Fisher’s interpretation of hauntology and the longing for a future that never arrived (though I don’t know if I’m fully on board with his criticism of contemporary retro-inspired media, on-point though some of it is). The result is I often I wonder whether the reactions I feel towards media products that rely on nostalgic capture is either market-generated or sincere.

That’s not to say I didn’t like this album. On the contrary, I absolutely loved it. Even given its late release, it’s probably had more listen-throughs than any other album to come out this year for me. I missed out on the first round of pre-orders and my holiday-frugal mind has me hesitant to throw down for the vinyl repress (FYI, my birthday *is* coming up, friends!).

The thing is, this album is packed with shots of that sehnsucht feeling. You hear it in that short 4-note guitar refrain after the chorus in “Where I Want to Be,” or in the gorgeous angelic vocals of “Pages Turn” that embrace that sort of reverberating, church choir-like chorus often associated with 80s music.

Both tracks are standouts for me. “Where I Want to Be,” a single from Lawrence, Kansas, band Start, I think really defines the album — capturing that wistful playfulness I often associate with twee and jangle pop. It also perfectly encapsulates the DIY foundations that the genre was building upon — lo-fi and imperfect, boasting lyrics capturing simple notions of young romance with undertones of escapism.

“Pages Turn,” a seminal moment in the compilation, seems to carry more the markings of where the genre would evolve — cleaner production, more seemingly anthemic and layered in its verse-chorus-verse structure. The single, from the Barbara Manning-fronted 28th Day, also deals with themes of love but, as if signaling not just growth in sonic maturity, also features lyrics dealing with the desire to move on from a romance who’s time had come to an end. Obviously, as a compilation, there was no direct collaboration between the artists when the songs originally came out for the completed album. But as a manner of arrangement, the placement of “Where I Want to Be” at the beginning and “Pages Turn” later in the middle represents an illustrative way of displaying the trajectory of jangle pop as a whole.

While romance does feature heavily as a theme across tracks, several other songs reckon with a variety of issues tied to the cultural moment the genre was coming of age in. While there is the sort of punk nihilism perhaps seen in the surreal lyrics of tracks like Crippled Pilgrim’s “Black + White” (a minor key refuge in a sea of upbeat offerings), others like Absolute Grey’s “Remorse” delve beautifully into themes of existential longing, the search for meaning, and even suicide.

Those are just a handful of standouts. At 28 tracks, this compilation has a wide offering to delve into. Other standouts include tracks like Bangtails’ “Patron of the Arts” — anchored by the frontman’s ferocious vocals. The Darrows’ “Is It You” showcases the genres close ties to the post-punk sound and a more melancholy sort of approach. And “You and Me,” from The Strand, is just a delightfully bouncy romp with a groovy synth progression that loops you in.

I think the rediscovery of music like this is obviously invaluable — bringing to the surface a cultural moment that had long been overlooked and that tells the story of a scene that managed to carve out its own radical space. The stories of DIY-oriented musical movements, from punk to hip-hop, has always fascinated me with how it emerges both organically and as a reaction to standards in the mainstream.

While I question the nostalgic impulses that might compel consumers towards certain media products today, I do think there is something that can be gleaned from the notion of a collective memory that surrounds a particular sound. While I’m not certain where one necessarily begins and ends with a study like that, the rediscovery of moments like those captured on Strum & Thrum does do a good service in expanding the ground upon which that search can begin.