When I started this whole “Photo Log” series, I envisioned it as a kind of chronicle while I learned the ropes of film photography and how that, in turn, would help me develop my photography skills in general. Like maybe around entry 70 or so I’d finally look back and say “wow, I’ve really come a long way.”

Or it’ll still be amateur hour, who knows.

Of course, that means not every entry in this log is one where I would be showing off work I was especially proud of or that every lesson is one I meet successfully. One part of learning is the process of fucking up, after all.

This is one of those entries!

Shooting film these days of course means looking to and engaging with the past a lot — particularly when it comes to the peripherals you use. I shoot mainly using a Canon A-1 that was manufactured between 1978 and 1985 and, aside from the gnarly Canon cough it has and one brief scare, mine has largely functioned well — likely buoyed by my constant appeals to the cosmos that each press on the shutter doesn’t cause it to suddenly fall apart.

But when it comes to the actual film, photographers these days still have access to new products — even new releases in the case of entities like CineStill. But while it is nice to still have access to the fresh stuff, I think any film photographer will answer with a nervous chuckle at how expensive even a single new roll can be.

That’s why some opt to shoot expired film, though not entirely because it’s cheaper (more on that in a bit).

I’d rather not get too much into the technical reasons behind film expiration and how photographers can compensate for it in this post, so instead enjoy this short explainer from my favorite film photography YouTuber.

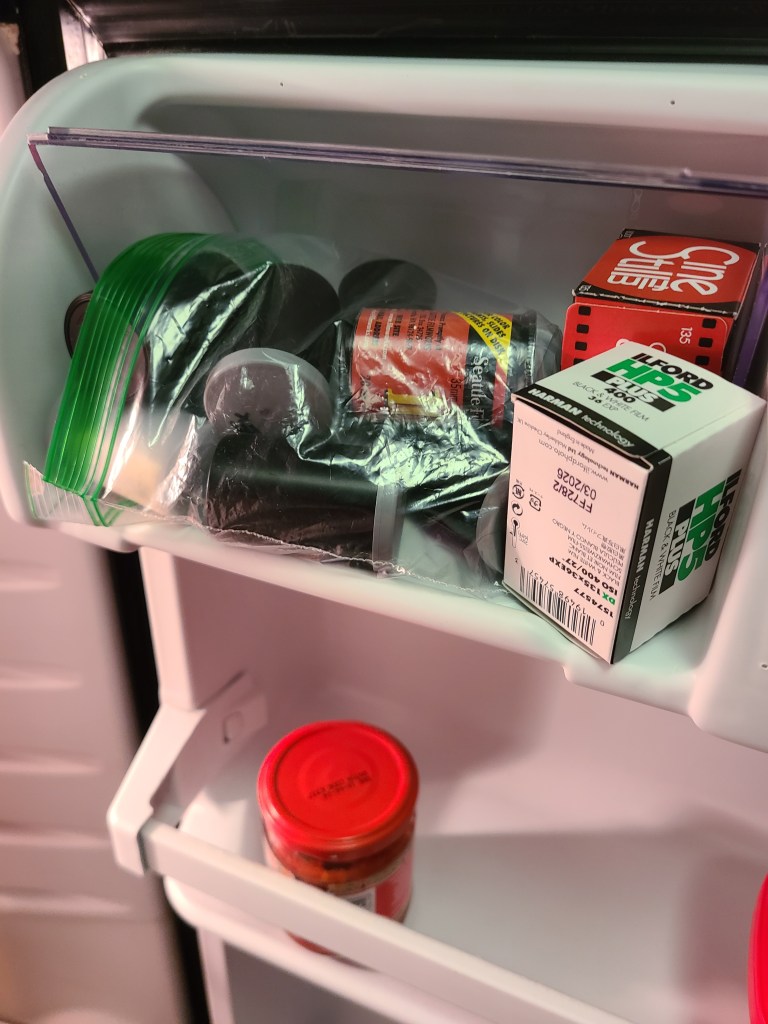

For a variety of reasons, I’ve come into the possession of a good deal of expired film. Most came from my mom, who found several unused rolls while cleaning that had expired mainly around 2003. Among these were a few rolls of Kodak Ultramax 400, Kodak Gold 200, and some exciting Kodak Max 800. I also recently purchased 3 rolls for cheap at a vintage market here in Austin — the most exciting of which was some Kodak Tri-X.

My understanding is that one of the biggest factors to determine how the film retains its quality past the expiration date is how it’s stored, hence why most photogs have some dedicated space in their refrigerator to slow down any degradation. But for the rolls in my possession, I’m pretty certain such steps were not taken.

So when I go on an outing, I usually take a couple of rolls with me — one color negative and one black and white, just to see what I’m feeling when I finally finish up the roll I’m on. One day this past October while I was exploring the nearby town of Georgetown to escape the ACL crowds, I towed along one of the expired rolls — the Kodak Gold.

“It’s finally time,” I thought to myself. To be honest, I approached it pretty naively.

The other aspect that draws photographers to expired film that I alluded to earlier is that expired film can produce some random, but cool results in how the colors of your image comes out. It’s absolutely kind of a game of chance if you don’t know how the film was stored previously, but most I’d seen were some color shifts and heightened contrast — some more radical than others but ultimately an image still was produced.

In my mind, I figured my results would hardly be any different. So when I popped in the roll of Kodak Gold, I figured I’d largely be just picking up from where I was leaving off from the fresh roll of Portra 400 I’d just wrapped up.

Nah.

My first mistake: I did not change my ISO settings. This has been a bad habit that I partly attribute to taking so long to get through a roll. I’ll sometimes spend weeks before I actually make it through one, so when it finally comes to change it out, I forget to adjust ISO settings on my camera if shooting outside the usual 400 range I seem to usually be in. Not to mention, if I understand correctly, I should have shot the 200-speed Gold at 100 or 50 to compensate for the degradation. I didn’t realize this mistake until I was well over halfway through the roll.

Still, in my naivety I thought that maybe everything would turn out fine. Again, my thought was that I was going to get at least SOME image out of it — just maybe the colors would be washed out or something.

Well my first indication that I might be wrong came when I reached out to the lab I was going with to develop the film, Gelatin Labs, and told them that I needed the roll developed for 400 ISO. They replied to say they would do so, but that it “might be beyond repair.”

But I still held out hope that not all was lost.

After the Thanksgiving holiday, Gelatin had a little sale over at their site for film processing. I always try to take advantage of these so I went ahead and purchased one to use for later, only to notice I had a $6 credit to my account. This was the second sign to me that there was a bigger issue — labs will generally give you a credit if the images on the roll turned out totally damaged.

I reached out to Gelatin and received a reply the following day, along with the scans of the expired Kodak Gold roll. I excitedly opened the scans first, still naively thinking that they must have simply just strayed a bit too far from a perfect exposure, but maybe the images still had a cool color effect on them.

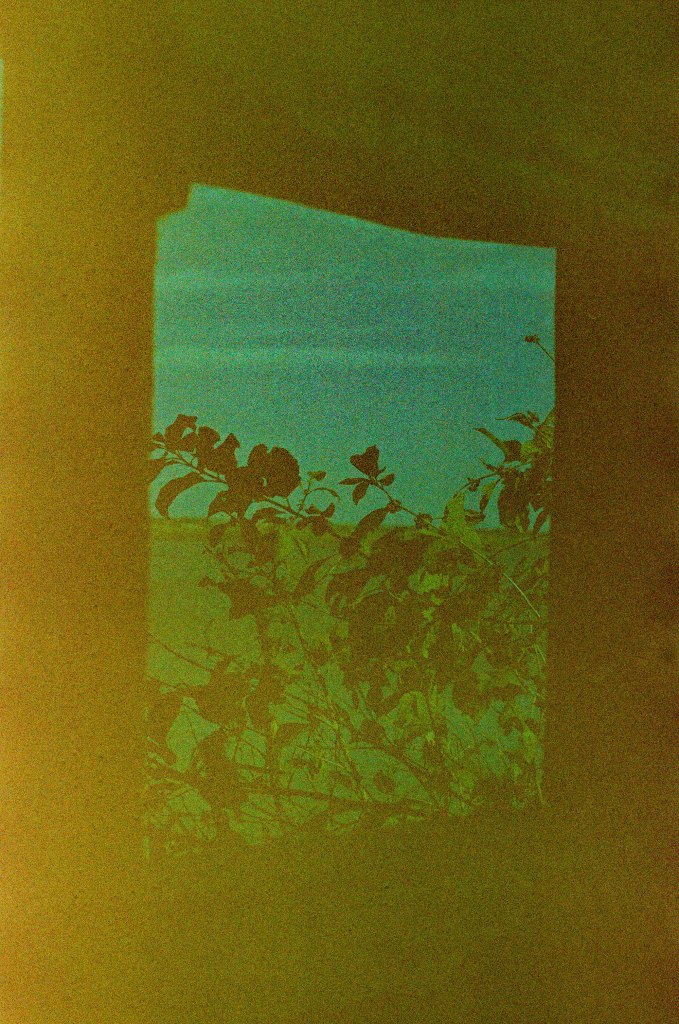

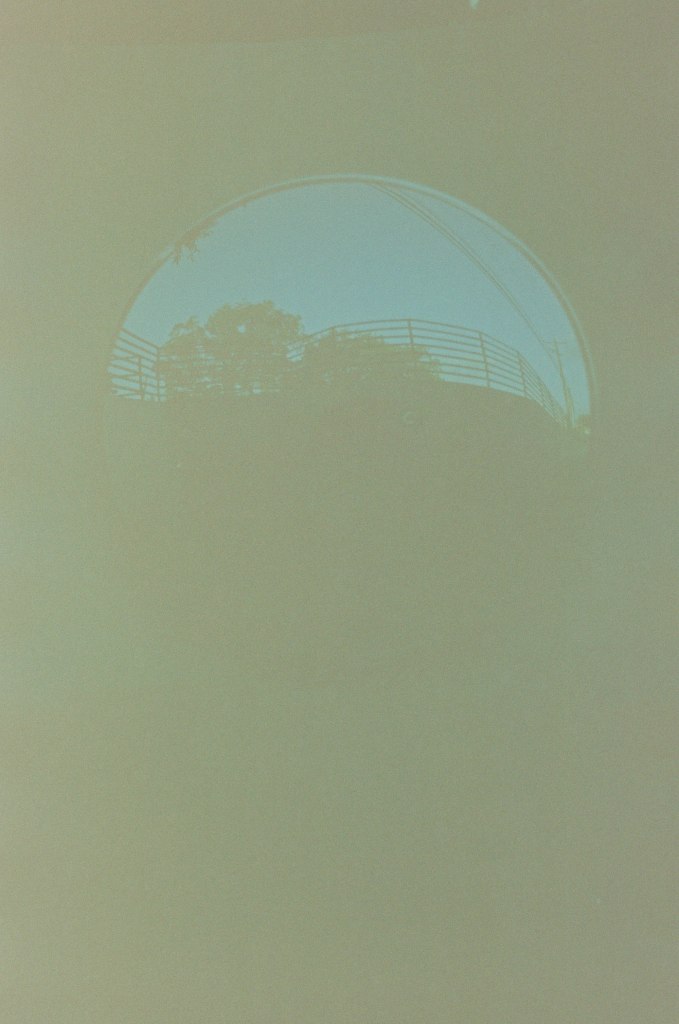

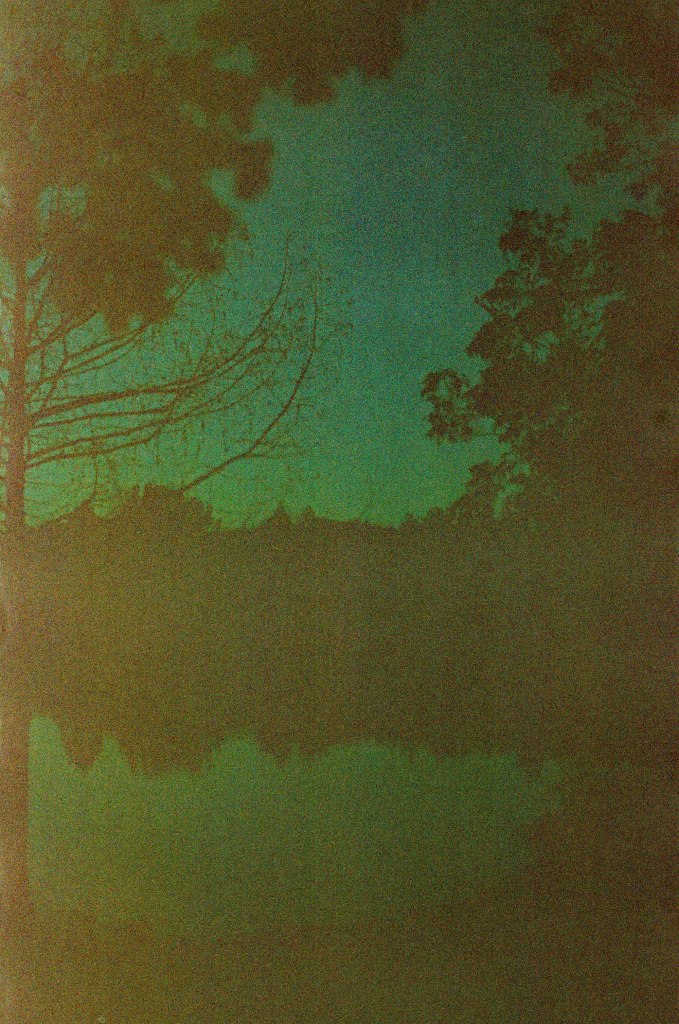

I was greeted by numerous scans with images that were hardly recognizable — badly faded and obscured by a murky haze. Even those taken under conditions I knew were well-lit were totally washed out.

The reply from Gelatin almost felt like scolding, though I’m sure it wasn’t intended — the gist being that expired film may be appealing, but fresh is where you get the best results. This was an obvious point, though one I wasn’t really expecting since I figured shooting on expired film was relatively common.

I did, however, attempt to salvage what I could through Lightroom. I essentially cranked the dehazing all the way up, messed around with exposure levels and sharpness, and did some tuning on the colors to at least unearth the image hidden in the fog.

Honestly, some images did end up appealing to me, even after being “fried extra crispy” as I’ve come to call it. And perhaps I also dig how some just look straight up old — weathered by time so that they come across more like an obscured memory. This, of course, taps into that nostalgia factor that I know was partly what drew me to the medium in the first place.

But, nonetheless, these images aren’t what I was expecting. Some that I was really looking forward to, like the shot of the skeleton piñatas, are far removed from what I was hoping for.

I can only chalk this roll up as something of a lesson learned, at least. I will likely shoot expired film again (I have all these rolls, after all) but I think they’ll certainly be saved for when I’m actually aiming for something a bit more experimental.

Anyways, thanks as always for reading. Feel free to leave any feedback or tips, as well as share any experiences you may have had shooting on expired film. I’d love to see what results you ended up with.

Peruse more photos from this roll in the slideshow at the end of this post, all developed and scanned by the aforementioned Gelatin Labs. I’ll include a few of the pre-edit versions at the end of the slideshow if you want to see more of how they originally turned out.

And per usual, enjoy a little playlist to go with this post.

Until next time.